|

Biography BARNEY, JOSHUA Joshua Barney (6 July 1759 – 1 December 1818) was an American Navy officer who served in the Continental Navy during the Revolutionary War. He later achieved the rank of commodore in the United States Navy and also served in the War of 1812. At the outbreak of the War of 1812, after a successful but unprofitable privateering cruise as commander of the Baltimore schooner Rossie, in which he captured the Post Office Packet Service packet ship Princess Amelia, Barney entered the US Navy as a captain, and commanded the Chesapeake Bay Flotilla, a fleet of gunboats defending Chesapeake Bay. He authored the plan to defend the Chesapeake, which was submitted to Secretary of the Navy, William Jones and accepted on August 20, 1813. The plan consisted of using a flotilla of shallow-draft barges, each equipped with a large gun which would be used in large numbers to attack and annoy the invading British, then retreating to the safety of shoal waters abundant in the Chesapeake region. Barney was commissioned as a captain in the United States Navy on 25 April 1814.[11] On 1 June 1814, Barney's flotilla, led by his flagship, the 49-foot (15 m) sloop-rigged, self-propelled floating battery USS Scorpion, mounting two long guns and two carronades, were coming down Chesapeake Bay when they encountered the 12-gun schooner HMS St Lawrence (the former Baltimore privateer Atlas), and boats from the 74-gun third rates HMS Dragon and HMS Albion near St. Jerome Creek. The flotilla pursued St Lawrence and the boats until they could reach the protection of the two third rates. The American flotilla then retreated into the Patuxent River where the British quickly blockaded it. The British outnumbered Barney by 7:1, forcing the flotilla on 7 June to retreat into St. Leonard's Creek. Two British frigates, the 38-gun HMS Loire and the 32-gun HMS Narcissus, plus the 18-gun sloop-of-war HMS Jasseur blockaded the mouth of the creek. The creek was too shallow for the British warships to enter, and the flotilla outgunned and hence was able to fend off the boats from the British ships. Battles continued through 10 June. The British, frustrated by their inability to flush Barney out of his safe retreat, instituted a "campaign of terror," laying waste to "town and farm alike" and plundering and burning Calverton, Huntingtown, Prince Frederick, Benedict and Lower Marlboro.[11] On 26 June, after the arrival of troops commanded by United States Army Colonel Decius Wadsworth, and United States Marine Corps Captain Samuel Miller, Barney attempted a breakout. A simultaneous attack from land and sea on the blockading frigates at the mouth of St. Leonard's creek allowed the flotilla to move out of the creek and up-river to Benedict, Maryland, though Barney had to scuttle gunboats No. 137 and 138 in the creek. The British entered the then-abandoned creek and burned the town of St. Leonard, Maryland.[11] The British, under the command of Admiral Sir Alexander Cochrane then moved up the Patuxent, preparing for a landing at Benedict. Concerned that Barney's flotilla could fall into British hands, Secretary of the Navy Jones ordered Barney to take the flotilla as far up the Patuxent as possible, to Queen Anne, and scuttle it if the British appeared. Leaving his barges with a skeleton crew under the command of Lieutenant Solomon Kireo Frazier to handle any destruction of the craft, Barney took the majority of his men to join the American Army commanded by General William Henry Winder where they participated in the Battle of Bladensburg. Frazier scuttled all but one of the vessels of the Chesapeake Bay Flotilla, which the British captured.[11] See Here For complete info on Joshua Barney GENERAL JACOB BROWNJacob Brown: Forgotten general of 1812UB historian Arthur Bowler says the U.S. leadership mistakenly thought the Canadians simply would surrender at the sight of American guns. Photo: Niagara Parks Commission

Prior to the commemoration of its 200th anniversary, the War of 1812 was a largely forgotten war, according to R. Arthur Bowler, UB professor emeritus of history. Yet despite recent attention, some of the war’s key figures remain obscure, including its most effective field commander, Gen. Jacob Brown.

r

“It’s always mystified me,” says Bowler. “Brown should have greater recognition.” There isn’t much in Brown’s pre-military life that would inform his destiny. He was a farmer from Northern New York whose most glowing accomplishment before the war was his success smuggling goods across the St. Lawrence River. He had served in the local militias, but he had neither significant training as a soldier nor any apparent interest in military leadership. In fact, Brown opposed the war. And his commission in the New York militia was based on both political connections and the fact that a high rank excluded him from participation in military parades, which he found especially distasteful and inconvenient for a frontier farmer. But John Armstrong, the U.S. secretary of war, was saddled with an incompetent corps of generals who had failed at Detroit, Queenston Heights, Chateauguay and Chrysler’s Farm. He was desperate to make a change. Bowler says the incompetence so evident in the war’s early years stemmed from a myth born out of the American Revolution. “There was a belief that victory in the Revolution could be attributed to the local militias—the farmer taking his musket down from over the mantelpiece to defeat the mightiest empire of its time,” Bowler explains. “That wasn’t the case. The Revolutionary War was won by George Washington’s regular troops and by the regular troops sent by France to help the United States.” Nevertheless, U.S. leadership was caught up in the mythology of the common man’s military might. “You think these guys would have been smart enough to understand their history,” says Bowler. “But they didn’t. They believed that the Canadians would surrender at the sight of U.S. guns, that victory, as Thomas Jefferson predicted, would be ‘a mere matter of marching.’” It wasn’t that the Canadians were all that eager to repel the American invaders. In fact, most of the people living in Southern Ontario at the time were not true loyalists, but Americans who settled there after the Revolution because they could get good land for the simple price of an oath of loyalty to George III. But there was the matter of several thousand British soldiers under General Isaac Brock and by 1814, Armstrong knew his older generals and their old ways could not adequately deal with that reality. He wanted younger generals and new ideas. Brown’s appointment is, however, ironic, considering that the mythology of the fighting farmer contributed to early American failures in the war and Brown himself emerged directly from the farm to lead U.S. troops. It is, in fact, a double irony. Brown’s command helped perpetuate the myth of the Revolution, while the overall lesson learned from the War of 1812 was that the militia victory was a myth and that America needed a standing, professional army. Brown also was a paradoxical figure. He was a disciplinarian, yet someone who relied heavily on the advice and counsel of his officers. “He was not an arrogant commander,” says Bowler. “He never assumed that rank made him right.” But he was bold, and he often ignored his superiors and their orders if he felt their instructions were outdated and irrelevant. “Remember that every commander was burdened by slow communication,” says Bowler. “The people in Washington were two months away from knowing what was happening on the spot.” Brown proceeded based on the circumstances of the moment. He also was aggressive and possessed an ability to visualize an area and quickly conceptualize a plan. “He had a very modern view of warfare,” notes Bowler. “He had experience as a surveyor and understood the relationship between geography and tactics.” Brown, in fact, probably had an easier time explaining his disregard for his superior’s orders than in dealing with some of his junior officers, notably Winfried Scott, Eleazer Ripley and Peter Porter. “These were men with big personalities,” says Bowler. “They wanted to be at the forefront.” Scott was a bit reckless, with a gift for accomplishing nothing more than amassing a staggering American casualty list. Ripley, meantime, was a brave man with slow feet, who often didn’t act quickly enough. “Porter was in between the other two,” says Bowler. “He was a half-military, half-civilian figure who could get away with doing things on his own.” Despite the unfavorable circumstance surrounding his command, Brown won three of the nine major U.S. victories in the war. Even his defeat at Lundy’s Lane is viewed as a tactical victory Yet, he is still largely ignored by history. “It’s not just Brown,” Bowler says. “People wanted to forget the war—or at least the very embarrassing details, such as by 1814, New England was considering secession from the union; none of the aims proclaimed by Congress in its declaration of war were achieved; or that American armies invaded Canada (we don’t do that sort of thing, do we?). And even worse, were repulsed!” Bowler adds that people wanted to remember the War of 1812, simply, albeit inaccurately, as a second Revolutionary War that had the same outcome as the first. “That’s all people needed to know,” he says. Two hundred years later, however, people should know that Jacob Brown should be ranked among America’s greatest military commanders. |

|||||||

| Birth: | Jan. 24, 1749 |

| Death: | Oct. 12, 1828 |

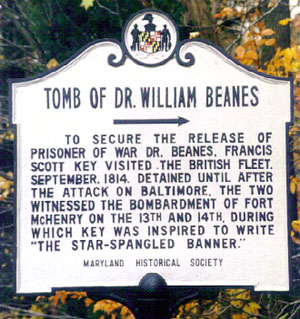

Patriot. He was a Surgeon to the Maryland Marching Militia and was entrusted in the safe keeping of the Maryland State Records during the Revolutionary War and War of 1812. It was feared that Annapolis would be attacked and burned so the records were sent to Upper Marlboro. Annapolis was spared of invasion during both wars but Upper Marlboro was invaded three times but with no destruction. As one unit was leaving the town two drunken stragglers were seen and out of disgust he arrested them without thinking about the safety of the destruction of the town and records. He was arrested and sent to Baltimore. The townspeople enlisted the help of Francis Scott Key and Colonel John Stuart Skinner in gaining his release. Being successful in obtaining that release, the three were heading back to Upper Marlboro when they witnessed the fiery attack on Fort McHenry. That attack inspired the writing of the Star Spangle Banner by Francis Scott Key. Without the arrest of Dr. Beanes and the loyalty the townspeople had towards him Francis Scott Key would never have been in Baltimore and the Star Spangle Banner would have never been written. |

|

BIOGRAPHIES

Isacc Chauncey, National and Black Rock, CT Hometown HeroHonored. Speaker: Elizabeth Oderwald, president Connecticut

Society U.S. Daughters of 1812

On October 13, 2012 an event was held in which this date was proclaimed Commodore Isaac Chauncey Day in Bridgeport, Connecticut. This video shows part of the history ceremony which was held by the Black Rock Community Council to honor Commodore Chauncey, had many accomplishments including working to end the War of 1812.

A plaque was placed at his birthplace. The following is what the plaque says:

BIRTHPLACE OF

COMMODORE ISAAC CHAUNCEY

1772 - 1840

U.S. NAVAL COMMANDER, GREAT LAKES

WAR OF 1812

FOUGHT IN BOTH WARS AGAINST THE BARBARY PIRATES

1801-1805 AND 1815

COMMANDANT OF THE BROOKLYN NAVY YARD

1807-1813 AND 1824-1833

PRESIDENT OF THE BOARD OF U.S. NAVY COMMISSIONERS

1837-1840

PLACED IN 2012 BY THE BLACK ROCK COMMUNITY COUNCIL AND

THE U.S. DAUGHTERS OF 1812

BETSY DOYLE A very good biography of this heroic lady is found on the Fort Niagara National Park Service Site. Click Here

LINK TO THIS FOR ARTICLE ON PUSHMATAHA

Pushmataha, 1824, Smithsonian American Art Museum

Tribe Choctaw

1815 – 1824

Born c. 1764

Macon, Mississippi

Died December 24, 1824

Washington, D.C.

Successor Oklahoma (nephew)

Native name Apushamatahahubi

Nickname(s) Indian General

Cause of death Croup

Resting place Congressional Cemetery, Washington D.C.

Pushmataha (c.1760's - 24 December 1824; also spelled Pooshawattaha, Pooshamallaha, or Poosha Matthaw), the "Indian General", was a chief of the Native American tribe of the Choctaws, regarded by historians as the "greatest of all Choctaw chiefs"[1]. Pushmataha was highly regarded among Native Americans, Europeans and white Americans for his skill and cunning in both war and diplomacy. Rejecting the offers of alliance and reconquest proffered by Tecumseh, Pushmataha led the Choctaws to fight on the side of the United States in the War of 1812. He negotiated several treaties with the United States. In 1824, he traveled to Washington to petition the Federal Government against further cessions of Choctaw land; he there met with John C. Calhoun and Marquis de Lafayette, and his portrait was painted by Charles Bird King. He died shortly thereafter and was buried with full military honors in the Congressional Cemetery in Washington, D.C.. Andrew Jackson marched in his funeral procession down Pennsylvannia Avenue.

ARTICLE ON PUSHMATAHA SEE Bottom of webpage has MARKING INFO

SEESEE